What Happened To Buddhism In India?

(PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS, IABS XVIII, TORONTO, AUGUST 20, 2017)

Richard Salomon

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 41 • 2018 • 1–25 • doi: 10.2143/JIABS.41.0.3285737

ABSTRACT

The reasons for the decline and disappearance of Buddhism from its Indian homeland have long been the object of controversy. It is generally agreed that the assimilation of ideas and practices from the Brahmanical-Hindu environment must have played a major part in weakening the institutions and distinct identity of Buddhism, but authors have differed as to whether this was a matter of “friendly embraces” or hostile persecution. Some representative or unusual examples of inscriptions illustrating convergences of Buddhism and Hinduism are presented, and some suggestions for new ways to approach the question are proposed.

1. Introduction

Here are the bare facts, known to everyone concerned: from about the early thirteenth century CE, Buddhism ceased to exist in the Indian sub-continent, with the exception of some isolated pockets in which it seems to have survived into to the sixteenth century. Hence the question that has been asked, over and over: How is it that Buddhism virtually died out in its home after thriving there for a millennium and a half, during which time it spread far beyond its Indian motherland to become a dominant religion in virtually all the rest of Asia?

This grand historical paradox has fascinated and vexed Buddhologists and historians since the beginning of the modern academic study of Buddhism in the nineteenth century. Yet for the most part it still remains a mystery. This is no doubt in part due to the usual problem of the insufficiency of the historically-oriented source materials which besets this, as most aspects of the historical study of Indian Buddhism. But there must also be deeper underlying problems, and I regret to have to confess that, after studying the opinions of many eminent scholars, I find myself no closer to an answer to the question. I therefore make no claim here to any revolutionary new insight or over-arching new theory. Rather, I begin this essay with an old question, and will end it with the same old question; my only hope is that I will be able to make the question a little more interesting, and perhaps to shed some light on the nature of the question itself. For part of my frustration with this issue and the scholarship on it (only a fraction of which can be referred to here) seems to result from what is perhaps a misguided framing of the question. This has typically been framed, explicitly or implicitly, in the form “Why did Buddhism die out in India?” That there cannot be a single answer to such an immense question is obvious, and more or less agreed to by all of the authors whom I have consulted, so they have typically presented their explanations in the form of sets of causes in various combinations and permutations. Typical of the most frequently alleged causes are the following:

- Buddhist institutions failed to establish deep roots and commitment among the laity. For example, Edward Conze thought that “relations with the laity were already precarious, and there at its base was the Achilles heel of the whole soaring edifice” (Conze 1980: 41).

- Buddhism was excessively centralized in large monastic institutions, figuratively or and literally walled off from the world. Thus, for instance, A. Skilton: “Buddhism seems to have become a religion for specialists, particularly monastic specialists occupying the increasingly grand universities” (Skilton 1994: 143).

- Buddhist institutions gradually lost the patronage of the kings, royal families, and wealthy lay donors on which they depended: N.R. Reat, “It appears that Indian kings and the laity gradually lost interest in financing Buddhism’s expensive monastic institutions” (Reat 1994: 77).

- Lasting harm was inflicted on Buddhist institutions by the persecutions of hostile kings and invaders such as Puṣyamitra Śuṅga, who offered one hundred dīnāras to anyone who would give him the head of a Buddhist monk,1 the Hun king Mihirakula, and King Śaśāṅka of Gau&a. In the words of L.M. Joshi, “One of the really potent factors contributing to the decline of Buddhism in the country [India] was royal persecution” (Joshi 1977: 319).2

- Internal decay, corruption, and depravity of various sorts – often associated with the rise of Tantrism and the Vajrayāna – have been associated with the demise of Buddhism, albeit mostly by authors of earlier generations, before a more open-minded attitude toward the Vajrayāna developed in recent decades. Thus no less a scholar than the venerable P.V. Kane quotes, approvingly, Swami Vivekananda: “I have neither the time nor the inclination to describe to you the hideousness that came in the wake of Buddhism. The most hideous ceremonies, the most horrible, the most obscene books that human hands ever wrote or the human brain ever conceived, the most bestial forms that ever passed under the name of religion have all been the creation of degraded Buddhism” (Kane 1962: 1030).

- Sectarian divisions and other structural defects, including the absence of a central authority, have been cited as inherent weaknesses that in the long term undermined the survival of Buddhism: Thus K.T.S. Sarao: “The refusal of the Buddha to appoint any person as his successor … must have given opportunities to centrifugal tendencies … leading to the formation of different groups” (Sarao 2012: 71).

- Many authors, citing the Buddha’s prediction (in its best-known formulation) that the Dharma was destined to be forgotten in a thousand years as a self-fulfilling prophecy, refer to a so-called “death-wish” which is allegedly deeply imbedded in Buddhist tradition; thus Sarao, “Such a mind-set must have contributed towards the saṃgha not thinking or acting in terms of working towards a perennial survival of the Dhamma” (Sarao 2012: 271).

- Most authors cite, in one form or another, what are often imprecisely referred to as “Muslim invasions” – more accurately, the conquests of the Ganges-Yamuna doab by Turkish adventurers in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. These events are typically thought of in terms of a “coup de grâce” for Indian Buddhism, but there are some who maintain that it was a primary cause, most notably A.K. Warder: “The effect of the Arab and Turkish conquests was the destruction of most of the early schools of Buddhism” (Warder 1970: 517).3

- Finally and perhaps most convincingly, many authorities have invoked as the real cause of Buddhism’s decline the hostility of Hinduism in its various manifestations toward Buddhism, or its peaceful subversion thereof, or some combination of the two; I shall have more to say on this topic later.

Besides these frequently cited causes, various authors have from time to time proposed other explanations intended to supplement or even supersede the usual ones. To mention just one interesting example, Jaini argued that the development of the bodhisattva doctrine and its “enormous popularity worked for, rather than against, the destruction of Buddhism in India” as “the place of the historical Buddha himself was functionally usurped by these figures,” ultimately leading to a “subversive synthesis with Hindu belief and practice” (Jaini 1980: 86).

But what is rarely if ever addressed, is how, or whether, these alleged causes – all of which, I hasten to add, do have at least some validity – interacted. The strategy of invoking multiple causes for Buddhism’s decline is a virtual constant in the literature, and it seems to be simply assumed that they somehow interacted to have a cumulative effect; but this unspoken and perhaps unjustified assumption seems to me to weaken the entire structure of the argument. I have not been able to find any authors who address this problem in any more than a rather superficial way, typically by invoking the recurrent metaphor of late Indian Buddhism as a “sick man,” weakened by multiple “illnesses” – weak relations with the laity, loss of patronage, etc. – and finally done in by one last blow, namely, the “Muslim” invasions (see e.g., Pratt 1940: 113).

The comparative method too does not seem to bring us much farther toward a comprehensive explanation. For example, it has been observed by a few authors – most notably by R.C. Mitra (1954: 1), in an important publication that I will refer to in more detail later – that there is a curious parallel with Christianity, which, like Buddhism, conquered half of the world but in the meantime all but died out in its motherland. However, other than this broad and perhaps only coincidental similarity, the two cases are not really comparable, as the geographical, historical, and cultural circumstances entirely different. So this comparative line of explanation too leads to a dead end.4

2. Meta-theories: Thoughts on the decline of religions

It might be useful to look at the question in a broader theoretical framework, for example by asking bigger questions such as, “Why do religions die?” As far as I am aware, very little has been said about the death of religions in general or in comparative perspective,5 but there is a little-known exception in the works of the American philosopher of religion James Bissett Pratt. Pratt was the author of two relevant but forgotten essays. The first, in 1921, briefly posed the question “Why do Religions Die?,” and was printed in The Journal of Religion, appropriately enough, under the sectional rubric “Unsolved Problems.” The second, in 1940, proposes some answers to the question, under the title “Why Religions Die.” In the latter essay, after surveying the “deaths” of various major religions of the ancient world, Pratt enumerates, by way of conclusion, a list what he considers to be frequent causes of death. These include:

- Reabsorption into the mother faith, as in the case of Buddhism

- “Violence and persecution,” as in the case of Zoroastrianism in Iran

- “Intellectual and moral superiority of the victorious religion,” as in the case of the triumph of Christianity over paganism

- Conservatism and lack of elasticity, as in the case of ancient Egyptian religion (Pratt 1940: 121).

While it would be easy scoff at some of Pratt’s rather naïve and old-fashioned – nearly 80 years old – ideas such as the “inherent superiority” of certain religions (particularly of Christianity) over others, he nevertheless deserves some credit for being the first to even address the general question of why religions die. He also makes, in his introductory comments, the important observation that it is only natural that religions should die: “The surprising thing … is not that religions die, but that they live” (Pratt 1940: 97–8; cf. n. 5 above). For it must be remembered that there have been uncountable religions, or perhaps rather, potential religions which have not survived beyond infancy, or at best childhood; one need only read about the bizarre doings of the latest “wacky cult” to prove the point. Only a chosen few survive to live forever – which really means only until the present, for in the grand sweep of history all religions, perhaps, must meet their end, as most already have. If this seems a rash prediction, let us call to mind those religions which survived into maturity, or at least adolescence, and came close in their time to becoming world religions. The classic example is the Manichaean religion, which, along with Mithraism, was Christianity’s main rival as the successor to paganism. Had the winds of history blown in a different direction at some critical moments, one of these faiths, now forgotten to all but some dusty scholars, might have dominated the western world.

3. A closer look at the literature: a few selected examples

Turning back now to the case of Buddhism: I do not propose to review in any detail the vast literature on the subject, including several books and innumerable scholarly articles. Merely by way of a sampling and an overview, I will present a few examples of some particularly influential or interesting contributions to the subject. I begin with an essay by a very familiar figure, namely the redoubtable Monier Monier-Williams.

In his seventh Duff lecture in 1888, entitled “Changes in Buddhism and its disappearance from India,”6 Monier-Williams cited what he held to be an inherent paradox in Buddhist doctrine, such that “every doctrine he [Buddha] taught developed by a kind of irony of fate into a complete contradiction of itself.” For example, “the effect of the Buddha’s leading men to believe that all supernatural revelation was unneeded” led to their “attributing infallibility to the Buddha’s own teaching, and worshipping the Law of Buddhism … with all the ardour of enthusiastic bibliolatrists” (Monier-Williams 1889: 153–54). In order to survive, later Buddhism “dropped its unnatural pessimistic theory of life and its unpopular atheistic character and accommodated itself” to Hinduism (Monier-Williams 1889: 165). But “Buddhism, in parting with its ultra-pessimism and its atheistic and agnostic ideas, lost its chief elements of individuality” and “It simply in the end … became blended with the systems which surrounded it,” so that “what ultimately happened … was, that Vaishṇavas and Śaivas crept up softly to their rival by close and friendly embraces, and that … Buddhism gradually and quietly lost itself” (Monier-Williams 1889: 165, 166–67, 170).

For my next example, I jump ahead 65 years, to a much more developed stage of the study of Buddhism, manifested in R. C. Mitra’s aforementioned The Decline of Buddhism in India. It is, I think, generally agreed that this book, published in 1954 on the basis of the author’s dissertation written in Paris under the supervision of Louis Renou in 1949, remains in many respects the definitive work on the subject, especially as far as the basic collection of data is concerned. In this brief volume of 172 pages, Mitra compiled an enormous body of literary and especially inscriptional data bearing on the late phases and decline of Buddhism in India, and most of the many books and articles on the subject that have been published subsequently have relied heavily on Mitra’s material.

The body of the book is composed of a series of detailed regional surveys of the late stages of Buddhism, and concludes with a chapter on “Causes of Decline” (Mitra 1954: 125–64, chapter X). After reviewing some of the causes of decline which had been invoked by previous authors, such as persecution, internal corruption, sectarian division, weak relations with lay followers, and Islamic conquest, Mitra focuses on what he perceives as the inherent weaknesses of the Buddhist system of belief:

- Abstruse doctrines such as pratītyasamutpāda were “far too subtle to be ever comprehended by the common mind.”

- “The very moderation of Buddhism, its sane and severely rational outlook, made the religion … less acceptable to the masses.”

- “Another formidable handicap of Buddhism was its incurable pessimism.”

- “To the Indian mind, atheism was the original sin of Buddhism” (Mitra 1954: 161–63).

In short, according to Mitra, Buddhism was never suited to what he calls “the Indian mind,” which is innately and profoundly theistic and devotional, with the result that Buddhism – particularly Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism – was increasingly infiltrated by Hindu beliefs and practices, so that “The dividing lines got more and more blurred” (Mitra 1954: 157) until Buddhism essentially ceased to exist as a distinct entity.

There is in fact considerable evidence, as will be shown later, to support the notion that Buddhism’s disappearance was caused or at least promoted by its loss of distinct identity. But Mitra’s notion that Buddhism was inherently unsuitable to “the Indian mind” is problematic in several regards; for one thing, if this was so, why did Buddhism arise in India at all, and why did it win millions of followers for many centuries? I say this, not to diminish Mitra’s fundamental contribution to the question, but only to show how difficult – perhaps impossible – it is to formulate cogent explanations for Buddhism’s decline.

Thus although Mitra in the mid-twentieth century had access to a far greater corpus of textual and epigraphic information than did Monier-Williams in the late nineteenth, his conclusions are not very different from his predecessor’s. For instance, when he refers to “the process of strangling Buddhism by a friendly embrace,”7 we hear a distinct, though probably unconscious echo of the words of Monier-Williams, already quoted above: “Vaishṇavas and Śaivas crept up softly to their rival by close and friendly embraces, and … Buddhism gradually and quietly lost itself.”

Most of what has been written about the disappearance of Buddhism since Mitra has rested on various combinations and permutations of his basic set of proposed causes which have been summarized above, sometimes with the addition of a novel idea or two to the mix. For example, in K.T.S. Sarao’s recent (2012) The Decline of Buddhism in India: A Fresh Perspective, the author collects a great of information, some of it new and interesting and much of it inevitably not; and it must be said that in the end he still rests heavily on the foundation erected by Mitra. After reviewing the data and re-evaluating the old theories, he concludes with a five-fold “model for decline,” the five factors being:

- Concentration in urban areas and lack of a mass-base

- Dependence on mercantile communities for patronage

- “Intellectual snobbery” and “social aloofness”

- “Death-wish mentality”

- Infiltration of “brahmanical elements in the saṃgha” (Sarao 2012: 263–76).

There is indeed something new in the mix, particularly in Sarao’s stress on the first two of these five points; but in balance it is hard to avoid the impression that for the most part this is more a matter of shuffling the old cards than of bringing in new ones.

The same cannot however be said about Giovanni Verardi’s Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India (2011), which presents a refreshingly original, if controversial and questionable new treatment of the issue. In this book, the most recent major contribution to the question of the disappearance of Buddhism, Verardi argues vehemently and at length against the gentle, pacific imagery drawn by Monier-Williams, Mitra, and others. Moreover, unlike Sarao, he adduces a great deal of new material, especially from archaeology and art history. In place of Monier-Williams’ “friendly embraces,” he sees relations between Buddhism on the one hand and Brahmanism and Jainism on the other as an uninterrupted struggle, characterized at best by bitter rivalry and at worst by physical violence and murder. For Verardi, persecution of Buddhists was real and pervasive. For example, the legend of Puṣyamitra’s attempts to uproot and destroy the Buddhist saṅgha is for him no mere rhetorically exaggerated metaphor for a return under the new Śuṅga dynasty to royal patronage of Brahmanism, as it is understood by most modern historians, but rather brute historical fact: Puṣyamitra “started a campaign aimed at dismantling the Buddhist monasteries, that were the nerve centres of the open society” (Verardi 2011: 99).

Verardi’s presentation is throughout conditioned by an unapologetically Marxist view of how society and history work. In his view, “The core of the Brahmanical system” was “the preservation at any cost … of caste privileges,” whereas “late Buddhism had advocated the cause of the outcastes, rousing a real social war,” so that “if Buddhism was eventually defeated, it was because the revolt of the natives and of the untouchables ended in failure” (Verardi 2011: 40, 49, 57).

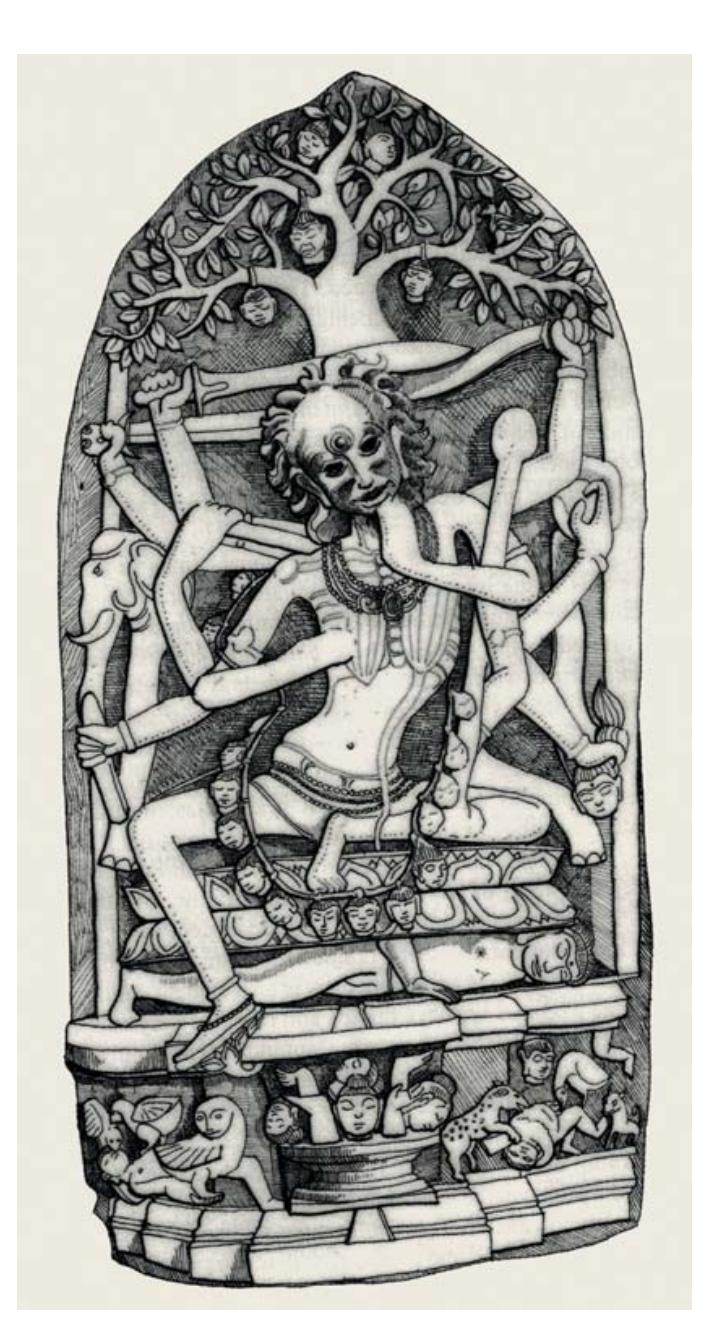

In support of his unconventional standpoint, Verardi adduces a large number of archaeological and artistic artifacts which, in his interpretation, are indicative of bitter and undisguised hostility toward Buddhists; for example, the image of Cāmuṇḍā sitting above the Buddha shown in figure 1. Such images, according to him, are to be “read” not as representations of myth, but rather as allegories for history (Verardi 2011: 222): “For iconographies to be so explicit and renouncing their semantic ambiguity, we must be facing a final showdown where the cards are on the table … The stele is … a first-hand documentation of what happened in places after the tenth century and a symbolic funeral of Buddhism: the Buddha lies dead” (Verardi 2011: 289, 292).

Figure 1: Cāmuṇḍā sitting atop the dead Buddha. (From Verardi 2011: fig. 13, p. 294.)

To an extent, Verardi’s arguments have force: he succeeds in adducing a considerable body of information indicating hostility and even violence on the part of Brahmanical society toward Buddhism, thereby providing a thought-provoking corrective to the naïve and sentimentalist “friendly embrace” of Monier-Williams and Mitra. But – as almost always seems to happen when a necessary corrective is applied – he has gone much too far in the other direction. The mass of evidence which he has compiled is – or so it seems to me – often forcibly shoe-horned into the preconceived Marxist-defined categories of class struggle, sometimes on the thinnest of grounds.

4. A closer look at the data: some epigraphic examples

Surely there must be a middle way between the diametrically opposed views of Monier-Williams and Mitra on the one side and Verardi on the other. Why, one has to wonder, does it have to be one way or the other? Such absolutist solutions simplistically reduce the vast diversity, complexity, and sheer scope of a millennium and a half of Indian history to a single entity with a single attitude, whether a “friendly embrace” or a relentlessly hostile confrontation. Why should we expect consistent policies over this vast span? Surely attitudes and situations changed from time to time, from place to place, nearly ad infinitum. How can these possibly be reduced to a single cause, or even a set of causes which somehow – mysteriously – acted in concert?

The frustration and dissatisfaction that arose when reviewing the literature of a century and a half on the disappearance of Indian Buddhism have led me, a little reluctantly but irresistibly, to the conclusion that it is not fruitful to address the question in term of “why.” The phenomenon is far too complex to be reduced, not only to a single cause, but even to a complex of interacting causes. For the remainder of this article I propose, therefore, to reformulate the question, not as a matter of “why?,” but rather of how Buddhism died out in India. So, in lieu of a real answer, I present below a few examples of inscriptional testimonies – a miniscule fraction of the whole body of relevant material – in order to show how they may help to illuminate the issue.8

Inscription A

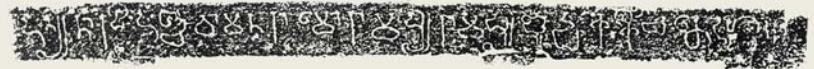

The first example concerns the familiar issue of the date of the acceptance of the Buddha as the ninth of ten avatāras of Vi!(u. This list is attested in a well-known inscription in the Ādivarāha-Perumāḷ temple at Mahābalipuram (Tamil Nadu),9 shown in figure 2, which reads:

Figure 2: The daśāvatāra inscription in the Ādivarāha-Perumāḷ temple. (From Krishna Sastri 1926, pl. I–C.)

(*matsyaḥ kūrmo var)āhasya narasiṃhaś ca vāmana<*ḥ>

rāmo rāmasya [sic] rāmasya [sic] buddha[ḥ] kalkī ca te daśa //(*Fish, tortoise), boar, man-lion, dwarf; [Paraśu]rāma, Rāma, [Bala-]rāma, Buddha, and Kalk): these are the ten [avatāras].

The importance of the epigraphic version of this particular verse, – which also occurs in several purāṇas10 as well as in some manuscripts of the Mahābhārata11 – is that, as is so often the case, it is the epigraphic record which provides at least an approximate terminus ante quem for the notion of the Buddha-avatāra; this, in contrast to the epic and purāṇic texts whose dates are impossible to pin down with any precision or certainty. The inscriptional version of the verse, in contrast, can be at least approximately dated on the grounds of paleographic estimation; the ornate late Pallava script of this record has been attributed to the late seventh12 or early eighth century (Sircar 1971: 194, n. 7).

So, we can at least be sure that the Buddha had been incorporated into the canonical list of avatāras by about that time.13 But it is important for our main subject to recall that the acceptance of the Buddha into the Vaiṣṇava pantheon was something of a grudging one. For the Buddha avatāra is explained in a well-known purāṇic legend according to which Viṣṇu incarnated himself as Buddha in order was to counteract the growing power of the asuras by confusing them with a false dharma.14 In this way, the threatening heterodox doctrine was co-opted into the Hindu/Vaiṣṇava world view, a development which justifies Mitra’s fittingly ambiguous image of Hinduism’s “strangling Buddhism by a friendly embrace.”

Inscription B

Similarly inclusivist attitudes are abundantly attested in other inscriptions, including Jaina as well as Hindu. For example, a Kannada inscription in the Prasanna-Gadādhara temple (Tumkur District, Karnataka) of the Hoysaḷa period (mid-12 century CE) has the following opening verse in Sanskrit:15

jayanti yasyāvadato ’pi bhāratī-vibhūtayas tīrthakrto ’pi + + + /

śivāya dhātre sugatāya viṣṇave jināya tasmai sakaḷātmane namaḥ //Victorious are the verbal powers of the Ford-maker, though he does not speak: homage to that Victor, (who is) Śiva, the Creator [Brahman], Sugata [Buddha], and Viṣṇu – the soul of all!

Inscription C

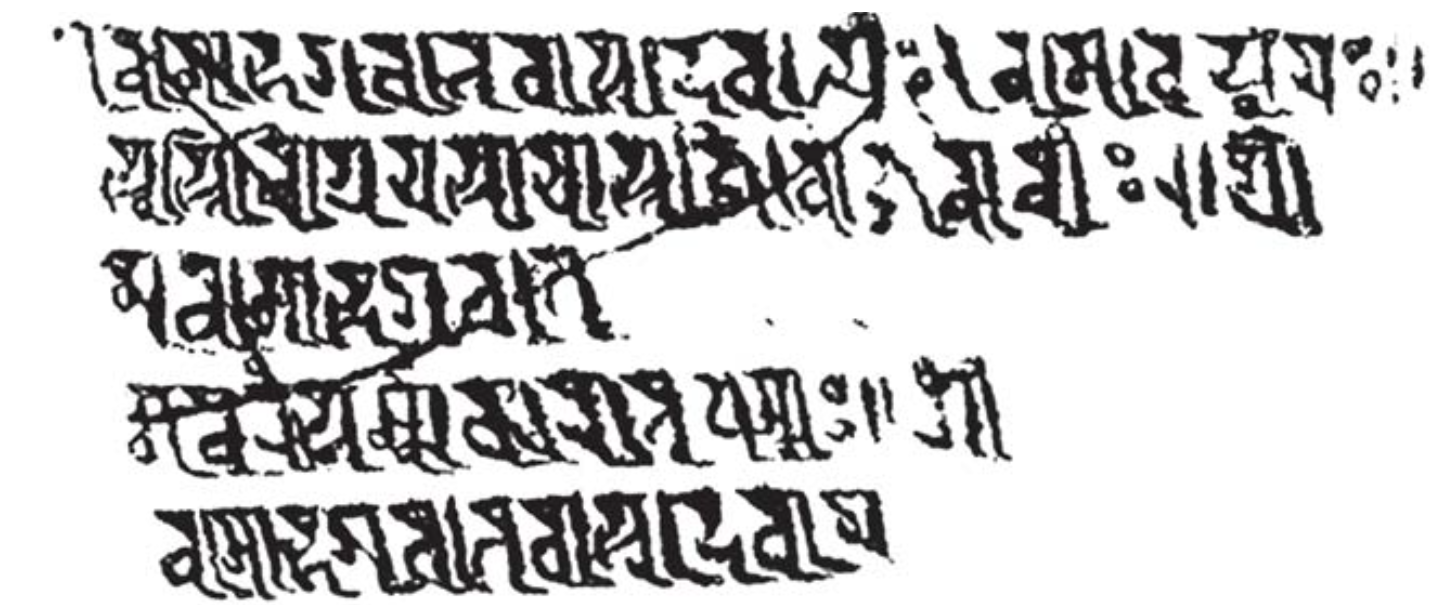

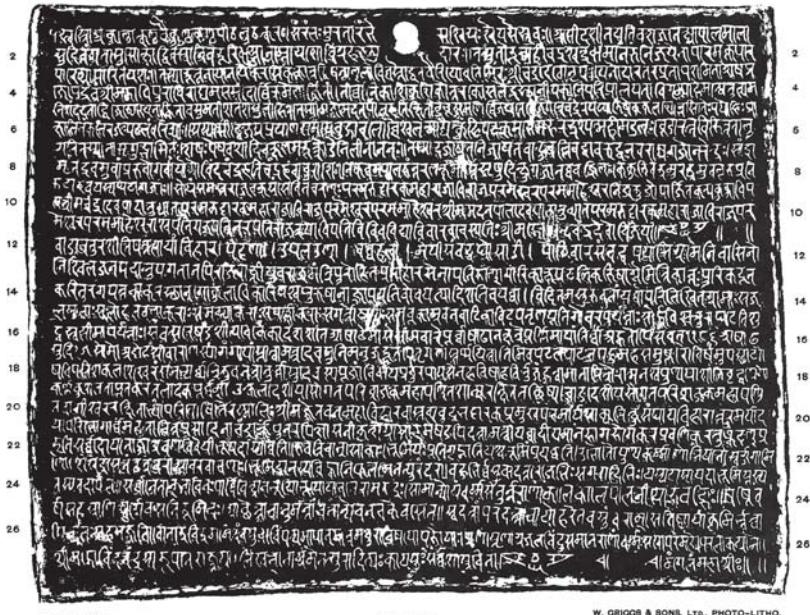

A unique inscription on a tortoise shell, found in the village of Vajrayo-ginipur in Dacca District, Bangladesh, is another remarkable document illustrating the intersection of Buddhist and Hindu beliefs.16 It reads, according to D.C. Sircar’s improved edition:

Figure 3: Inscription on a tortoise shell from Vajrayoginipur, Dhaka District, Bangladesh. (From Bhattasali 1939–40: pl. III.)

śrī namo bhagavate vāsudevāya / namo buddhāya /

svasti niśreyasāyāstu jino janānāṃ // śrī-

ma [sic] namo bhagavate

manaṃrasarma kārita dharmma // śi [sic]

namo bhagavate vāsudevāyaŚri. Homage to Lord Vāsudeva. Homage to the Buddha.

May the Jina be for the well-being of the people. Śri.

Homage to the Lord.

[This] dharma was made by Manaṃrasarmma [?].

Homage to Lord Vāsudeva.

Sircar comments that the inscriptions “no doubt point to a rapprochement between the worship of Vāsudeva and that of the Buddha” (Sircar 1949: 104 = 1971: 194). This much is clear from the direct juxtaposition of declarations of homage to Vāsudeva (i.e., Kṛṣna) and Buddha. But what, we are left to wonder, was the nature of this “rapprochement”? For example, are we to see this as evidence of Buddhism being absorbed into Vaiṣṇava Hinduism, or the other way round?

And there is more to the matter: why are these peculiar inscriptions written on, of all things, tortoise shell, this being, to the best of my knowledge, the only such cases in the vast corpus of Indian inscriptions? But actually, the peculiar material itself answers the question, for there has existed in West Bengal, even into modern times, a local cult17 of a deity known as Dharma whose image takes the form of a tortoise. According to S.K. Chatterji, the association of the local tortoise god with “Dharma” derives from a folk-etymological connection with an Austric word *daram or the like (Chatterji 1945: 79–80). In any case, the ethnographic data shows that the “dharmma” cited in the inscription refers to the tortoise-shell on which it is engraved, conceived as an image of the god Dharma.

Thus we have in this curious document a three-way confluence of beliefs from Buddhism, from mainstream Vaiṣṇava Hinduism, and from local folk religion. In this case at least, the “absorption” theory, according to which Buddhism was absorbed, or as some might say, reabsorbed into the Brahmanical/Hindu milieu from which it had arisen some fifteen centuries earlier, seems to have some validity. In fact, the next inscription will demonstrate the same point cast in a broader light.

Inscription D

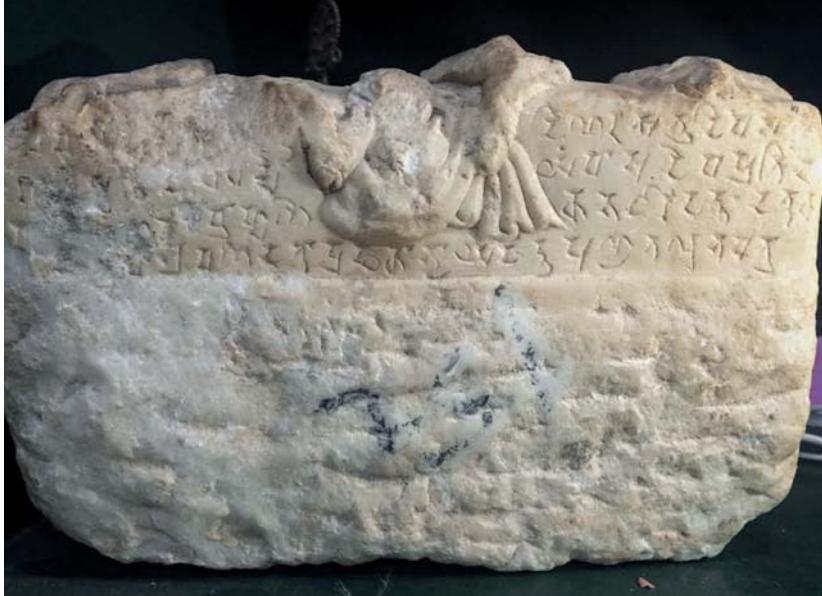

The juxtaposition, if not identification – we cannot know exactly how its author conceived of their relationship – of Buddha and Vāsudeva in the tortoise-shell inscription is hardly surprising, given its late date. But another, as yet unpublished inscription seems to indicate that the veneration of Vāsudeva by Buddhists had already begun much earlier, and in a far distant part of the Indian world. The inscription in question is on the base of a white marble image, of which only the feet and a portion of a hanging garment survive. The provenance of the object, which is in private hands in Pakistan, is not securely known, but it is likely to have come from at or near the site of B)rko,-Ghwa(&ai in Swat, on the basis of its similarity to another fragmentary pedestal which was found at the same site.18

Figure 4: Inscribed marble pedestal from Pakistan. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Kenoyer.)

The purpose of the fragmentary inscription19 was to record the dedication of an image of Vāsudeva, as shown by the text at the end of the second line, clearly reading vāsudeva-pratimā. But what is remarkable about the inscription is the distinctly Buddhist phrasing. First, the text straddling the hem of the hanging garment in the middle of the second line reads deyadharmmo yaṃ, “this is the pious gift [of …].” Second, the inscription apparently ends at the right side of the fourth line with yad attra puṇya ta X bhavatu, “Whatever merit there is in this, may it be [for …].”20 Both of these expressions are so characteristic of Buddhist donative inscriptions21 that we can hardly doubt that this is a Buddhist record22 – that is to say, an inscription recording a pious donation in or to a Buddhist institution, and in a Buddhist cultural context.

In and of itself, it is not surprising to find Vāsudeva mentioned in a Buddhist inscription, for we have just seen that this has been attested in later Buddhist records. The surprise is to find it in this one, which is datable on paleographic grounds23 to around the sixth century CE, that is, some five centuries earlier than the tortoise shell inscriptions from Bangladesh. So this new inscription not only shows us that Buddhists were venerating Vāsudeva/Kṛṣṇa at an earlier time than might have been expected, but also that this practice prevailed in the geographical extremes of the continent, from modern Pakistan in the far northwest to the eastern fringe of the Indian world in what is now Bangladesh. Thus the infiltration of paradigmatically “Hindu” cults in Buddhism cult practice appears to have been wider and deeper than is usually thought.

Inscription E

For a last epigraphic sample, we return to the late phase of Indian Buddhism and to a well-known but particularly interesting inscription, namely the Saheṭh-Maheṭh copper plate of the Gāhaḍavāla king Govindacandra, dated Vikrama saṃvat 1186 = 1128–9 CE, This inscription, first published by D.R. Sahni in 1911, was found at the archaeological site of Saheṭh-Maheṭh, which has been definitively identified with ancient Śrāvastī, the capital of the Kosala kingdom of King Prasenajit and one of the most important shrines of Buddhism, where the Buddha spent much of his teaching life. The inscription provides in several regards a remarkable picture of the state of the Dharma at a critical moment in its last decades in northern India, during the rule of one of the last great Hindu kings of the northern heartland. Among its several points of interest is the juxtaposition in it of Hindu and Buddhist motifs, with the starkest contrast and yet in the most intimate relationship.

Figure 5: Saheth-Maheth (Śrāvastī) copper plate of Gāhaḍavāla Govindacandra, 1128–9 CE. (From Epigraphia Indica 11, plate facing p. 24.)

The plate begins with the usual maṅgala verse of Gāhaḍavāla inscriptions:

akuṇ-hotkaṇ-ha-vaikuṇ-ha-kaṇ-hapī-ha-lu-hatkaraḥ /

saṃrambhaḥ suratārambhe sa śriyaḥ śreyase stu vaḥ //May the excitement of Śrī [Lakṣmī] at the inception of their loveplay, as her hands caress the throat of Vaikuṇṭha [Viṣṇu] whose desire is irresistible, be a blessing to you!

Thus the document begins with a verse whose sentiments are at once quintessentially Hindu and about as un-Buddhist as one could imagine. This verse is followed by the usual long genealogical preamble, after which the text turns, in the sixteenth line, to the actual matter at hand, namely the donative formula. This portion begins with a detailed descrip- tion of the king’s elaborate ritual preparations for the ceremony:

On this day, after bathing in the Ganges here at Vārā(as), satiating all of the mantras, gods, sages, humans, ghosts, and ancestors, paying his respects to the burning-rayed sun which easily slashes through the masses of darkness, worshipping the one [Śiva] who wears the crescent moon on his crest, and praying to Vāsudeva, savior of the three worlds …24

– once again, archetypically Hindu in every word and thought.25 The text then announces the real matter at hand, namely a royal land grant of six villages, not to the usual learned brahmans as in thousands of other copper plate charters, but rather to the saṅgha of the Mahāvihāra at Śrāvastī. The king explains that he did this because he had been “gratified by the Buddhist monk and great scholar Śākyarakṣita from the land of Utkala and by his student, the Buddhist monk and great scholar Vāgīśvararakṣita from the Coṣa land.”26

So here we find, on the surface at least, Hinduism and Buddhism living together happily and harmoniously hand-in-hand; and this, quite literally, since we know from another important Gāha&avāla inscription27 that King Govindacandra’s wife Kumaradev) was a devout Buddhist. So we can suspect that it was she who provided the motivation for her husband’s largess to the Dharma, notwithstanding his personal ideological stance as an orthodox Vaiṣṇava Hindu.

It is also of interest that the two Buddhist mahāpaṇḍitas who won the favor of the king (or rather, of his wife) and thereby inspired the donation were by no means locals, but rather hailed from regions far distant to the south, namely Utkala in Odisha and “the Coḷa land,” that is, the Tamil country. Such references to travels across vast distances by Buddhist teachers and followers are found quite frequently in inscriptions of the late Buddhist centuries (that is, from about the ninth to twelfth centuries). At first blush, this might seem to suggest the continued vitality of Buddhism in this period, but it can also be seen to point in the opposite direction. For such inscriptions are typically found at major pilgrimage centers and holy places, such as Śrāvastī in the present case, Nālandā, and especially at Bodh Gaya, and this can be taken to suggest that Buddhism had shrunk into a limited number of strongholds in and around its most holy and historic places. For example, the inscriptions on the Kurkihar bronzes (Gupta 1965: 125–59) testify to a community of Buddhist monks and lay followers from as far away as Kāñcī in the Tamil country at the shrine of Kukkuṭapāda in Bihar during the Pāla period; the Ghosrawan inscription (Kielhorn 1888) records the career of a monk from Nagarahāra in Afghanistan who became the abbot of the Nālandā monastery; and several late inscriptions at Bodh Gaya, such as the inscription of Mahānāman, a native of Sri Lanka (Fleet 1888: 274–78, Tournier 2014), attest to the settlement there of pilgrims from various distant lands.

One thus gets the impression that Buddhism was at this point contracting into its traditional strongholds – returning to its roots, as it were. In broad terms at least, the distribution of Buddhist inscriptions of the later centuries does point in this direction. This reminds us of the theory, often invoked in connection with the disappearance of Buddhism in India, that Buddhism tended to wall itself into its great monastic institutions such as Nālandā and Vikramaś)la, effectively cutting itself off from the surrounding communities. The geographical details are different in these two developments, but in both we can discern a process of contraction and reduction in the geographical and institutional scope of late Indian Buddhism.

5. What have we learned?

Not very much, perhaps. Many months spent reviewing the scholarly literature have been, in the end, somewhat disappointing. After sipping, over and over again, a lot of old wine in new bottles, or occasionally tasting some new wine but often finding its flavor slightly “off,” I have reluctantly come to the conclusion that posing the question “Why did Buddhism die out in India?” is one that remains and always will remain without a cogent answer. All of the factors which are typically invoked are to some degree true, but each one is insufficient in and of itself; nor has anyone has been able to formulate a pratītyasamutpāda for them collectively, that is, an explanation of how they might have acted in concert to achieve the actual outcome. The question, in short, is too big, too complex to ever yield a satisfactory answer; there can never be a single master solution.

But for all that, it is still a question that is worth asking, especially if, as proposed at the outset, we approach it in terms of “how” Buddhism withered and died in its homeland, rather than in terms of the unanswerable “why.” I have here presented a tiny sampling of relevant information from the vast and widely scattered data bearing on the question, and these items, along with many others that could have been cited, do tend to support the notion that Buddhism was increasingly assimilated to and thus absorbed into that complex of belief systems which we call, for lack of a better term, “Hinduism.” This, as we have seen, is not at all a new idea, having been long ago adduced, albeit in what nowadays must seem a somewhat naïve manner, by M. Monier-Williams, among others; so, if we have to pick one “best” answer from the grab-bag presented in the first part of this paper, it would have to be this one.

In conclusion, I would certainly not suggest that any ambitious young Buddhist scholar – or, for that matter, any learned senior savant – undertake another comprehensive study of the decline of Buddhism. This would hardly be likely to be conducive to enlightenment. Any brave soul who nevertheless wishes to confront the matter would be better advised to approach it in terms of a close-up case study of some particular aspect – geographical, chronological, or methodological – of the entire problem.28 Here a carefully chosen and judiciously conceived study could well lead to new insights which are applicable to the larger question. Even though the larger question can never be answered, that does not mean that it should not be asked. Such a question is of value insofar as it stimulates our thoughts and illuminates what we know and do not know about late Indian Buddhism. With this said, I leave the challenge to the next generations of scholars, should any among them may be brave enough to take it up.

References

Primary Sources

Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Maharṣivedavyāsapraṇītaṃ Śrīmadbhāgavatamahāpurāṇam. Vikrama 2008. Gorakhpur: Gītāpres.

Divyāvadāna. E.B. Cowell and R.A. Neil (eds.) 1886. The Divyâvadâna. A Collection of Early Buddhist Legends. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matsya Purāṇa. Matsyapurāṇam. 1907. Ānandāśrama Sanskrit Series 54. Poona: Ānandāśrama Mudraṇālaya.

Mahābhārata. Kumbhakonam edition: T.R. Krishnacharya and T.R. Vyasacharya (eds.). 1906-14. Sriman Mahabharatam. A New Edition Mainly Based on the South Indian Texts with Footnotes and Readings. 19 vols. Bombay: Javaji Dadaji’s “Nir(aya-Sāgar” Press, Poona Critical Edition: Vishnu S. Sukthankar et al. (eds.). 1933-59. The Mahābhārata for the First Time Critically Edited. 19 vols. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

Secondary Sources

Bhattacharya, G. 1987. “Dāna-Deyadharma: Donation in Early Buddhist Records (in Brāhmī).” In Marianne Yaldiz and Wibke Lobo, eds., Investigating Indian Art: Proceedings of a Symposium on the Development of Early Buddhist and Hindu Iconography Held at the Museum of Indian Art Berlin in May 1986. Veröffentlichungen des Museums für Indische Kunst 8. Berlin: Museum für Indische Kunst/Staatliche Museen, Preußischer Kulturbesitz: 39–60.

Bhattasali, N.K. 1939–40. “5. Archaeological Section: (a) Sculpture and Epigraphs.” Annual Report of the Dacca Museum for the year 1939–40: 5–8.

Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. 1945. “Buddhist Survivals in Bengal.” In D.R. Bhandarkar et al., eds., B.C. Law Volume. Part 1. Calcutta: The Indian Research Institute: 75–87.

Chhabra, Bahadur Chand and Govind Swamirao Gai, eds. 1981. Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings. Revised by Devadatta Ramakrishna Bhandarkar. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum 3. Delhi: The Director General, Archaeo- logical Survey of India. (Revised edition of Fleet 1888.)

Conze, Edward. 1980. A Short History of Buddhism. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Fleet, John Faithfull. 1888. Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and Their Successors. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum 3. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. (See also the revised edition by Chhabra and Gai 1981.)

Gail, Adalbert J. 1969. “Buddha als Avatāra Vi (us im Spiegel der Purā(as.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Supplement I, 3: XVII. Deutscher Orientalistentag vom 21. bis 27. Juli 1968 in Würzburg. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag: 917–23.

Gupta, Parmeshwari Lal. 1965. Patna Museum Catalogue of Antiquities (Stone sculptures, metal images, terracottas and minor antiquities). Patna: Patna Museum.

Hinüber, Oskar von. 2004. Die Palola Ṣāhis: ihre Steininschriften, Inschriften auf Bronzen, Handschriftenkolophone und Schutzzauber . Materialen zur Geschichte von Gilgit und Chilas. Antiquities of Northern Pakistan, Reports and Studies 5. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Jaini, Padmanabh S. 1980. “The Disappearance of Buddhism and The Survival of Jainism: A Study in Contrast.” In A.K. Narain, ed., Studies in the History of Buddhism. Papers presented at the International Conference on the History of Buddhism at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, WIS, USA, August, 19–21, 1976. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation: 81–91.

Joshi, Lal Mani. 1977. Studies in the Buddhistic Culture of India (During the 7th and 8th centuries A.D.). 2nd ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Kane, Pandurang Vaman. 1962. History of Dharmaśāstra (Ancient and Mediæval Religious and Civil Law in India). Vol. V, part II. Government Oriental Series, Class B, no. 6. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

Kielhorn, F. 1888. “A Buddhist Stone Inscription from Ghosrawa.” Indian Antiquary 17: 307–12.

Konow, Sten. 1907–08. “Sarnath Inscription of Kumaradevi.” Epigraphia India 9: 319–28.

Krishna Sastri, H. 1926. Two Statues of Pallava Kings and Five Pallava Inscriptions in a Rock-Temple at Mahabalipuram. Memoirs of the Archaeological Society of India 26. Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch.

Lamotte, Étienne. 1988. History of Indian Buddhism from the Origins to the Śaka Era. Translated by Sara Webb-Boin. Publications de l’Institut Orientaliste de Louvain 36. Louvain-la-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain, Institut Orientaliste.

Lüders, Heinrich. 1940. “Zu und aus den Kharo ,h)-Urkunden.” Acta Orien- talia 18: 15–49.

Lüders, Heinrich. 1961. Mathurā Inscriptions. Unpublished Papers Edited by Klaus L. Janert . Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Philologisch-historische Klasse, Folge 3, Nr. 47. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Mitra, R. C. 1954. The Decline of Buddhism in India. Visva-Bharati Studies 20. Santiniketan: Visva-Bharati.

Monier-Williams, M. 1889: Buddhism, in its Connexion with Brāhmanism and Hindūism, and in its Contrast with Christianity. New York: Macmillan and Co. Pratt, James Bissett. 1921. “Why Do Religions Die?” The Journal of Religion 1: 76–78.

Pratt, James Bissett. 1940. “Why Religions Die.” University of California Publications in Philosophy 16(5): 95–124.

Reat, Noble Ross. 1994. Buddhism: A History. Berkeley CA: Asian Humanities Press.

Rice, B. Lewis. 1904. Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. XII: Inscriptions in the Tumkur District. Mysore Archaeological Series. Bangalore: Mysore Government Central Press.

Robinson, Richard H. and Willard L. Johnson. 1977. The Buddhist Religion. A Historical Introduction. 2nd ed. North Scituate MA: Duxbury Press. Rocher, Ludo. 1986. The Purāṇas. A History of Indian Literature, Vol. II, Fasc. 3. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Sahni, Pandit Daya Ram. 1911–12. “Saheth-Maheth Plate of Govindachandra; [Vikrama-] Samvat 1186.” Epigraphia Indica 11: 20–26.

Sanderson, Alexis. 2009. “The Śaiva Age. The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism During the Early Medieval Period.” In Shingo Einoo, ed., Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series 23. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo: 41–349.

Sarao, K.T.S. 2012. The Decline of Buddhism in India. A Fresh Perspective. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

Schneider, Johannes. 2015. “Eine buddhistische Sicht auf den Buddhāvatāra.” Berliner Indologische Studien/Berlin Indological Studies 22: 87–102.

Sen, Sukumar. 1945. “Is the Cult of Dharma a Living Relic of Buddhism in Bengal?” In D.R. Bhandarkar et al., eds., B.C. Law Volume. Part 1. Calcutta: The Indian Research Institute: 669–74.

Sircar, Dines Chandra. 1949. “Two Tortoise-shell Inscriptions in the Dacca Museum.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Letters 3(15): 101–08.

Sircar, D[ines] C[handra]. 1963–64. “Three Early Medieval Inscriptions.” Epigraphia Indica 35: 44–54.

Sircar, D[ines] C[handra]. 1971. Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Skilton, Andrew. 1994. A Concise History of Buddhism. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Srinivasan, Doris Meth and Lore Sander. 1997. “Visvar.pa Vy.ha Avatāra: Reappraisals Based on an Inscribed Bronze from the Northwest Dated to the Early 5th Century A.D.” East and West 47: 105–70.

Srinivasan, Doris Meth. 2016. Listening to Icons, Vol. I: Indian Iconographic & Iconological Studies. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Taddei, Maurizio. 2003. On Gandhāra: Collected Articles. Edited by Giovanni Verardi and Anna Filigenzi. Collana “Collectanea” III. 2 vols. Naples: Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale.”

Tournier, Vincent. 2014. “Mahākāśyapa, His Lineage, and the Wish for Buddha- hood. Reading Anew the Bodhgayā Inscriptions of Mahānāman.” Indo- Iranian Journal 57: 1–60.

Truschke, Audrey. 2018. “The Power of the Islamic Sword in Narrating the Death of Indian Buddhism.” History of Religions 57: 406–35.

Verardi, Giovanni. 2011. Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India. New Delhi: Manohar.

Warder, A.K. 1970. Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Footnotes

-

Divyāvadāna, no. XXIX (Aśokāvadāna), p. 434: yo me śramaṇaśiro dāsyati tasyāhaṃ dīnāraśataṃ dāsyāmi. For further references see Lamotte 1988: 387–92. ↩

-

Most historians nowadays deny that persecution played a significant role in the demise of Indian Buddhism, but Giovanni Verardi is a notable exception, as will be dis- cussed below (part 3). ↩

-

For the most recent critique of the widespread notion that Islamic invaders were responsible for the death of Buddhism, and in particular of Warder’s extreme formulation thereof, see Truschke 2018, especially p. 430. ↩

-

One might also compare the Zoroastrian religion, which has virtually died out in its homeland in Iran but survives, albeit in small numbers, in India. But here too, the circumstances are very different from those that affected Indian Buddhism. ↩

-

A small but noteworthy exception in the Buddhological literature is Robinson and Johnson 1977: 124: “It is not unnatural that Buddhism should have died out in India. Mithraism and Manichaeism, widespread and powerful in their day, perished, yet scholars are not overly amazed.” ↩

-

Published in Monier-Williams 1889: 147–71. ↩

-

Mitra 1954: 118; here he is referring to the friezes in the Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa temple at Hosahaḷalu (ca. 1240 CE), where images of the Buddha are mingled with those of “Rāma, Paraśurāma, Halāyudha, etc.” ↩

-

The fundamental importance of inscriptions to this (as to any historical issue in pre-Islamic India) hardly needs explanation or justification; this was eloquently put by R.C. Mitra, who aptly described them, in a characteristic bon mot, as “isolated points of light to illume [sic] an expanding darkness of centuries” (Mitra 1954: 36). ↩

-

Krishna Sastri 1926: 5–6 and pl. I–C. Cf. also, for example, Rocher 1986: 107, 111. ↩

-

E.g., Matsya Purāṇa 285.6c–7b. ↩

-

The verse appears in the Kumbhakonam edition of the Mahābhārata (XII.348.2) but not in the other editions, and it was not accepted into the main text of the Poona critical edition, where it was relegated to the notes after XII.326.71 (vol. 16, p. 1859); cf. Gail 1969: 917, 923. ↩

-

Rocher 1986: 107 (following Krishna Sastri 1926: 4). ↩

-

This is not, however, the end of the story, for it has recently been pointed out by Johannes Schneider (2015: 88) that a similar verse is attested in the Tarkajvālā of the Buddhist author Bhavya/Bhāvaviveka, who lived between 500 and 570 CE. So we have here an encouraging case in which one of the standard “facts” of Buddhist history has been refined by recent textual research. ↩

-

E.g. Bhāgavata Purāṇa X.42.22ab: namo buddhāya śuddhāya daityadānavamohine. ↩

-

Rice 1904: 7 (text section), 3 (translation section). ↩

-

The inscription was first published by N.K. Bhattasali (1939–40: 7–8); an improved version was published by D.C. Sircar (1949), and a revised version of the latter article was printed as part II (pp. 189–200) of chapter XII, “Decline of Buddhism in India,” in Sircar 1971. ↩

-

Apparently centered in Burdwan District (Sen 1945: 669, Sircar 1971: 195). ↩

-

See Taddei 2003: II.586–87 and figs. 13–14. I wish to thank Anna Filigenzi for bringing this reference to my attention. ↩

-

For the present context, I have not undertaken a complete edition of the inscription, which must await a future occasion, but only wish to mention the points in it that are particularly relevant to the issues at hand. ↩

-

The wording here is an abbreviated form of the typical formula for sharing the merit of a donation, which would read in full as, for example, yad attra puṇya tad bhavatu sarvasattvānām anuttarajñānāvāptaye ’stu. Presumably the formula was left incomplete because the engraver ran out of space; compare a possibly similar case in Lüders 1961: 113 (§78). But I am unable to explain the unusual sign between ta and bhavatu, which is noted here with “X.” It can hardly be meant to represent a vowelless d, as might be expected from its position. It somewhat resembles certain forms of the numeral 4, but that has no place here. Could it be some sort of abbreviation marker, indicating the deletion of the rest of the beneficiary formula? (The verb bhavatu usually comes before the intended purpose, but in at least one early inscription [Lüders 1961: 62] (agrapratyaśatāye bhavatu sarvvasatvānāṃ [hita]sukhā[rthaṃ]bhavatu) it follows.) ↩

-

Compare, for example, von Hinüber 2004: 177–86. ↩

-

Deyadharma “pious gift” and its variants are strongly characteristic of Buddhist inscriptions (see Lüders 1940: 24–25 and Bhattacharya 1987), but also occur occasionally in non-Buddhist inscriptions; see the exceptions noted by Lüders, to which should now be added the inscription on a Vaiṣṇava image of the fifth century CE (Srinivasan and Sander 1997 ≅ Srinivasan 2016: 153–216). But in the inscription at hand here, the collocation of the term deyadharma with the yad atra puṇyam … formula makes it certain that the inscription is Buddhist. ↩

-

The relatively early date is proposed on the grounds of, for example, the older (tripartite) form of ya. The script is comparable to that of the inscription on the Ganeśa image from Gardez, Afghanistan, which D.C. Sircar (1963–64: 44) dated, with characteristic conservatism, to the sixth or seventh century. The inscription introduced here was originally dated, but unfortunately most of the dating formula, including the prior part which would have stated the year and month, is lost in the obliterated left side of the first line. The right side of the line reads diṇe [sic] 9 attra divase (“… day 9; on this day …”). ↩

-

Lines 17–18: … adyeha śrī-vārāṇasyāṃ gaṅgāyāṃ snātvā mantra-deva-muni-manuja-bhūta-pitr-gaṇāṃs tarppayitvā timira-pa-ala-pā-ana-pa-u-mahasam uṣṇarociṣaṃm [sic] upasthāyauṣadhipati-śakala-śekharaṃ samabhyarccya tribhuvana-trātur vāsudevasya pūjāṃ vidhāya … ↩

-

For other examples of Brahmanical formulae in inscriptions recording donations to Buddhists, see Sanderson 2009: 116 and n. 256. ↩

-

Lines 19–20, utkaladeśīya-saugataparivrājaka-mahāpaṇḍita-śākyarakṣita-tacchiṣya-coḍadeśīya-saugataparivrājaka-mahāpaṇḍita-vāgīśvararakṣitābhyāṃ paritoṣitair asmābhiḥ … ↩

-

The Sarnath stone inscription of Govindacandra’s queen Kumaradev) (Konow 1907–08). ↩

-

Truschke, in an article on related topics which was published shortly before this one (2018: 433–35), reaches partially similar conclusions: “Instead of analyzing ‘Indian Bud- dhism,’ we are better off talking about Indian Buddhists … It is perhaps more useful to ask what happened to specific Buddhist communities in specific parts of the subcontinent … [M]aking the questions and answers more specific and people-focused may help scholars do away with the unfounded presumption that there is a single life cycle to Indian Buddhism as a tradition.” ↩